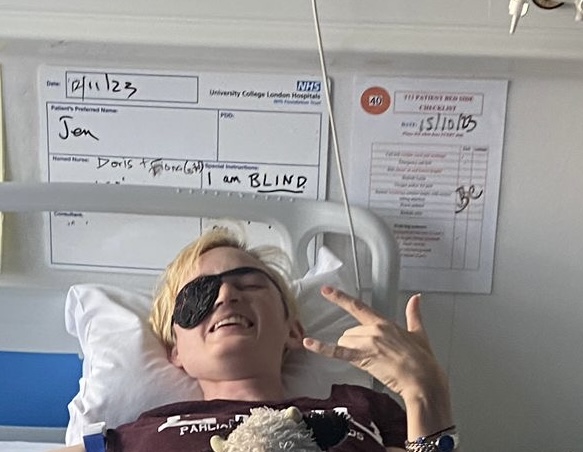

I was determined to keep making my way to and from the bathroom on my own, but my level of success hinged on whether things were where I expected them to be. There were some very scary moments.

The hospital is an ever-changing environment, and with no one really making note of the fact that there was a blind patient, it meant that things remained quite chaotic. For some reason, night times were the most disorientating. To be fair, that’s true of hospitals whether you’re blind or not.

There was one bathroom that I knew the layout of, and could get my way around. Then one night on my way to it, I was intercepted by a nurse who grabbed me without warning, spun me around, and rushed me off down the corridor to another bathroom, saying my usual one was blocked and that there was a sign on the door saying so. She deposited me in the strange new bathroom and told me to pull the alarm cord when I was done. This new toilet was the opposite way around and I went in circles trying to work out where everything was.

A few hours later when I went to go again, I called the HCA (health care assistant), who told me my usual bathroom was fine, and that I could use it. And so happily, I did. Then the next morning I was told it absolutely was not usable and that it was a biohazard and needed a full cleaning before it was safe to use. I tried not to think about it too much, though I would have preferred the HCA hadn’t just fobbed me off and sent me into a bathroom that was not fit for use. I guess she couldn’t see the sign on the door either…

When it finally was back in action, things had been moved around and there was a chair in the middle of the floor for me to crash into. When I asked the nurse what I kept tripping over in the middle of the bathroom, she said, ‘that’s just a chair… you just need to walk around it…’ It took me quite a while to get reorientated and I certainly lost some confidence in the whole situation.

Even just a bay curtain being pulled back was enough to stop me from being able to orientate myself and I would set off and suddenly find myself not where I thought I was. I worried I might jump into bed with someone else.

Thankfully I was in a bay next to the brilliant D, who always had my back. She would be there with an encouraging word, or watch over me as I ventured forth on my own, making sure to check in, or to let me know where I’d ended up if I’d got off course. And she was always on standby for a compassionate pep talk when it was all getting on top of me. She would remind me that although clinging to my independence whenever possible is important, ‘night-time is not the time to fight, baby girl. Just ring your bell, accept the help, and let them lead you there.’

And so I did.

Between D and my guardian angel G, and my friends dropping in, although sitting alone in the dark was extremely lonely and isolating, I also wasn’t alone. And I had Clarence, of course.

Food was a bit of an issue too. I try to generally eat pretty healthily, but the hospital menu is mostly white bread, pasta, rice and sugar. I used to be able to eat anything I could cut up (so I could get it in my mouth and chew with my few remaining back teeth – I can’t bite into anything thanks to my dentures). Suddenly overnight I couldn’t really use a knife and fork anymore. Plus no one really had the time to read the whole menu to me and describe the format of each meal. Luckily it was not my first rodeo, and I remembered a chicken salad from my last internment two years before. So every lunch and dinner it was soup, a banana, and the roast chicken salad (which consisted of 4 slices chicken breast, 5 sliced cherry tomatoes, a few bits of cucumber and a plate of lettuce). Then friends brought me a few snacks here and there – blueberries, cashews, and once a packet of hot-smoked salmon which I devoured unceremoniously using my fingers.

On the Sunday, my friend, Sarah, was visiting me, and she asked if I’d seen the Occupational Therapy team. I asked who they were… She explained that they might be able to help with the whole blindness thing. So when the nurses came around on Monday morning, I asked if someone was going to come help me with the fact I just suddenly went blind. They thought for a minute and said ‘would you like the Occupational Therapy team to come and see you?’

Yes, I said, that would be good. However, when they turned up the OT team knew nothing about blindness whatsoever, nor did they know anything about me as a patient. The first thing they asked me was how much I could see out of my right eye… Silence hung between us for a moment before I answered slowly, ‘I don’t have a right eye…’ They were very nice though (one of them was even Australian) and I helped them out a bit and explained a few things to them. They walked me to the bathroom, then they went off to Google blindness. I’d asked them where I could get a stick from, thinking it might be something they gave me, but they had no idea how I could get one.

Then Rosa turned up, and for a short while I was able to feel almost like myself again as we laughed and chatted and hugged. Who was I without my sight? Although my visits from my friends were everything to me and I didn’t want them to ever leave, there was always a moment nearing the end of their visits, where I felt suddenly very isolated, alone, and far away – I think it was the fear that I would be on my own again. But with plenty of time left on Rosa’s visit on Monday, the PICC Line team flitted in and asked if I might like another PICC Line.

Yes please.

The first chemo I’d had was fine to go through a regular cannula, but my second one would need a PICC Line. The people doing the PICC were very chill and fun, and we were all laughing. I was really glad Rosa was there with me. We both took one of my Lorazepams and we were ready to go.

I worried that getting a PICC line might be a bit scary without being able to see what was going on. But with Rosa there and the brilliant PICC team talking and laughing me through it, everything went very smoothly.

It always makes me laugh when the people doing the PICC check that the person with me – Rosa – isn’t squeamish. They said they usually make sure any emotional support humans sit down, but we didn’t have a spare seat.

‘Oh, it’s fine, I’ve actually had one myself…’ she said.

Anyway, something finally went smoothly thank goodness, and with the new PICC line happily sitting in my arm, Rosa headed off to leave me to my own devices for the evening, to listen to my audiobook, eat my evening chicken salad, and to grapple with the bathroom.

Hi Jen, I am full of admiration for you and the way you manage new challenges. Best wishes Sheila

LikeLike

What a journey and so well written! Sending goodness!

LikeLike

What a nightmare! So sorry you are going through all this while depending on overworked, undertrained, clueless hospital staff. The Tories have a lot to answer for, not least hollowing out the NHS. I’m only partially blind, crippled by a neurological disease, with stage IV cancer, and I know how terrifying it is to try to survive in even good hospitals. Hugs.

LikeLike

I’m smiling…It always makes my day when I get a blog post from you Jen! Sending hugs to You and Clarence…You’re an absolute trooper Babe, xx

LikeLike

You might find it helpful to contact the RNIB. They’ve got a shop where you could buy a white stick, and they can give you advice about other things, such as what other gadgets might help you, such as talking thermometers. I’ve got one of those.

They’ve got a helpline. The number’s 0303 123 9999.

Hopefully the occupational therapy team will come up with something though.

I’m blind myself, so I use a white stick, or more specifically a long cane. I find it helps in unfamiliar rooms where there are tables and chairs in the way if I hold it upright with the tip near the ground and move it across my body in step with my walking, so it’ll hit anything in my way so I’ll know to avoid it, rather than possibly sliding underneath it so I won’t know an obstacle’s there so quickly if I were to use it the way I would outdoors – the way people are taught to use it – when I slide it along the ground in front of me to detect steps and uneven ground as well as obstacles in my way.

LikeLike